memory practice

against forgetting, against genocide

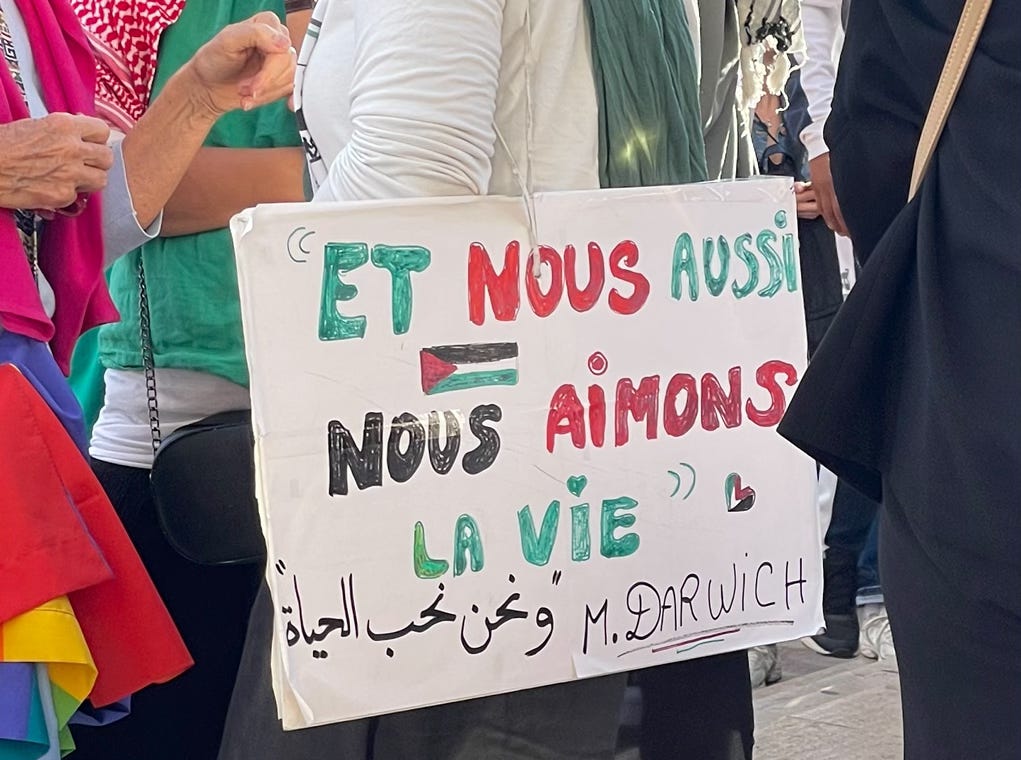

A week grew into a month, then into two months, and is now one hundred and ten days old. That’s the age of the occupation forces’s indiscriminate carpet bombing of Gaza. A bombing supplied and funded by western nations and their taxpaying residents killing more than 20,000 people, likely closer to 30,000 people, nearly half of which are children. For one hundred and ten days, we’ve witnessed a genocide in plain view with hourly streams of rubble, tears, blood, dead bodies, whole and in pieces, un-abstracting notions of death and destruction. What to make of a time where death feels so frequent for Palestinians? And if we turn our gaze south and west, we find death and displacement persist in equally shocking amounts in Sudan and in Congo.

I’ve been trying to make sense of how to live in a time of so much death. And not passive and accidental deaths but rather a concerted, manufactured and multi-national effort towards killing. Maybe that’s what most contemporary death is anyhow. Even disease and climate crises filter through our socially constructed hierarchies of safety and deservedness.

“Racism, specifically, is the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death,” as Ruth Wilson Gilmore defines it succinctly and honestly. Another definition I return to is Saidiya Hartman’s: “[If] we think about the very definition of racism, it’s about the uneven distribution of death across a social field. It’s about a monopoly of life chances. It’s about vulnerability to premature death.”

I keep these definitions close so I can continuously remember the logics that are upholding these social fields and the sadistic killing that is deployed onto them. I have to remember the logics that created an artificial state shaped like stacks of military contracts on an occupied land free of mines but full of diamond cutters and contempt.

All this memory work is up against the enemy that is misremembering even dis-remembering, erasing the fact of killing and the historical and contemporary contexts for such killing. Soon after October 7th, 2023, I thought about the Patriot Act and Black Hawk Down, two pieces of 2001’s soft power and policy collusions that fueled the flames of islamophobia, a manufactured and profitable hatred that allowed America and its allies to kill, raid and make a business of war without any residual moral impunity on the global stage. Amidst all our nostalgia for the early 2000s, did we forget that part? Who could afford to forget?

Amnesia remains central to the American dream, even to the millennial, even to gen z. Forgetting is a steady career and a vacation overseas and a home decorated with sensible furniture and gadgets that spell comfort even as they collect dust. If we’re so privileged, forgetting can look indistinguishable from living. Close to the heart of an empire, we can live a life that artificially fractures and de-contextualizes our comforts away from the exploitation they’re born out of. And from the unnatural order of our lives, we can risk falling for the seemingly sensible and sage middle ground which “sees both-sides” of conflict. But is the middle as safe a place as we’re sold when it is bookmarked by genocide on one side and land sovereignty on another? In this scenario, in all scenarios of colonization, the judicious midpoint of those two possibilities is an occupation enforced by constant violence.

As anti-intellectual as the middle is, it is also free of morals though it sells itself otherwise. Morality, it turns out, is a frequent co-conspirator of dominant power. It’s a flimsy weapon regularly deployed against liberation and self-determination movements from presidential podiums and congressional hearing rooms, from CEOs and economists, in news headlines and op-eds, and most importantly, in the privacy of our imaginations. We the commoners, the careerists, the liberals—if we chose trace the tail all the way to the head of wars in the name of freedom, who would we consider violent or immoral?

A friend and former editor of mine shared Kwame Ture’s 1969 essay, The Pitfalls of Liberalism written in the middle of the Vietnam War. Ture does not flinch:

“The way the oppressor tries to stop the oppressed from using violence as a means to attain liberation is to raise ethical or moral questions about violence. I want to state emphatically here that violence in any society is neither moral nor is it ethical. It is neither right nor is it wrong. It is just simply a question of who has the power to legalize violence.”

Though it can clarify the frame, the good word has its limits. I even have a set of preferred words for that sentiment from Toni Cade Bambara and her 1970 essay On The Issue of Roles: “Mouth don’t win the war,” she writes. It’s better read in context as a daily affirmation:

“It may be lonely. Certainly painful. It’ll take time. We’ve got time. That of course is an unpopular utterance these days. Instant coffee is the hallmark of current rhetoric. But we do have time. We’d better take time to fashion revolutionary selves, revolutionary lives, revolutionary relationships. Mouth don’t win the war. It don’t even win the people. Neither does haste, urgency, and stretch-out-now insistence. Not all speed is movement.”

And so, that’s where I arrive from to my question of what to do with time amidst this killing. I’ve concluded that it is in my interest to be sober about the use words and the aesthetics of liberation versus their practice as Bambara warns. It would be unwise to think myself, ourselves, liberated through metaphors while materially maintaining the conditions of imperialism through each scale of relation we maintain—the one with ourselves, with those we say we love, and with the state. I think words have their best place in memory practice, in naming the dynamics we witness, those we aid and abet in, and tallying the destructions of the belligerent aggressors. In this killing time, I read to remember and I’m writing here to do the same. And I remember, memorize, cite and recite in order to act against the anti-memory forces of zionism and imperial power.

I’ve picked back up my habit of reading out loud because hearing my own voice vibrate and shake makes words a more physical experience. In December, I sat by my heater and read out loud this most clear-hearted and sobering essay by Fargo Nissim Tbakhi, Notes on Craft: Writing in the House of Genocide. The whole thing must be read, out loud if possible and a few times over. To quote an excerpt from it here would feel like interrupting a sharp arrow. So do read it in whole and in the order it was written. Write me, if you’d like, about where you felt the fletching end, where you saw the shaft give into the point.

It’ll take attention and effort to reject all the superficial ways to respond to complicity in genocide: feigning smallness, powerlessness, adopting a desperation not earned through blood or sweat, falling for the false promise of intellect that cynicism offers. Practicing memory, witnessing and memorizing, will keep me steadfastly curious and vigilant about ways to untangle myself* and others from small and large scales of relation that depend on abuse to exist.

*speaking of untangling myself from systems that rely on abuse, Substack has been passive to its users and readers’s plea to moderate hate speech on its platform. Though I don’t post regularly on here, I’m considering possibilities of where else I might think out loud and test the limits of digital community. I do hope those options become clear to me soon & I’ll inform you, the patient reader, as they do.